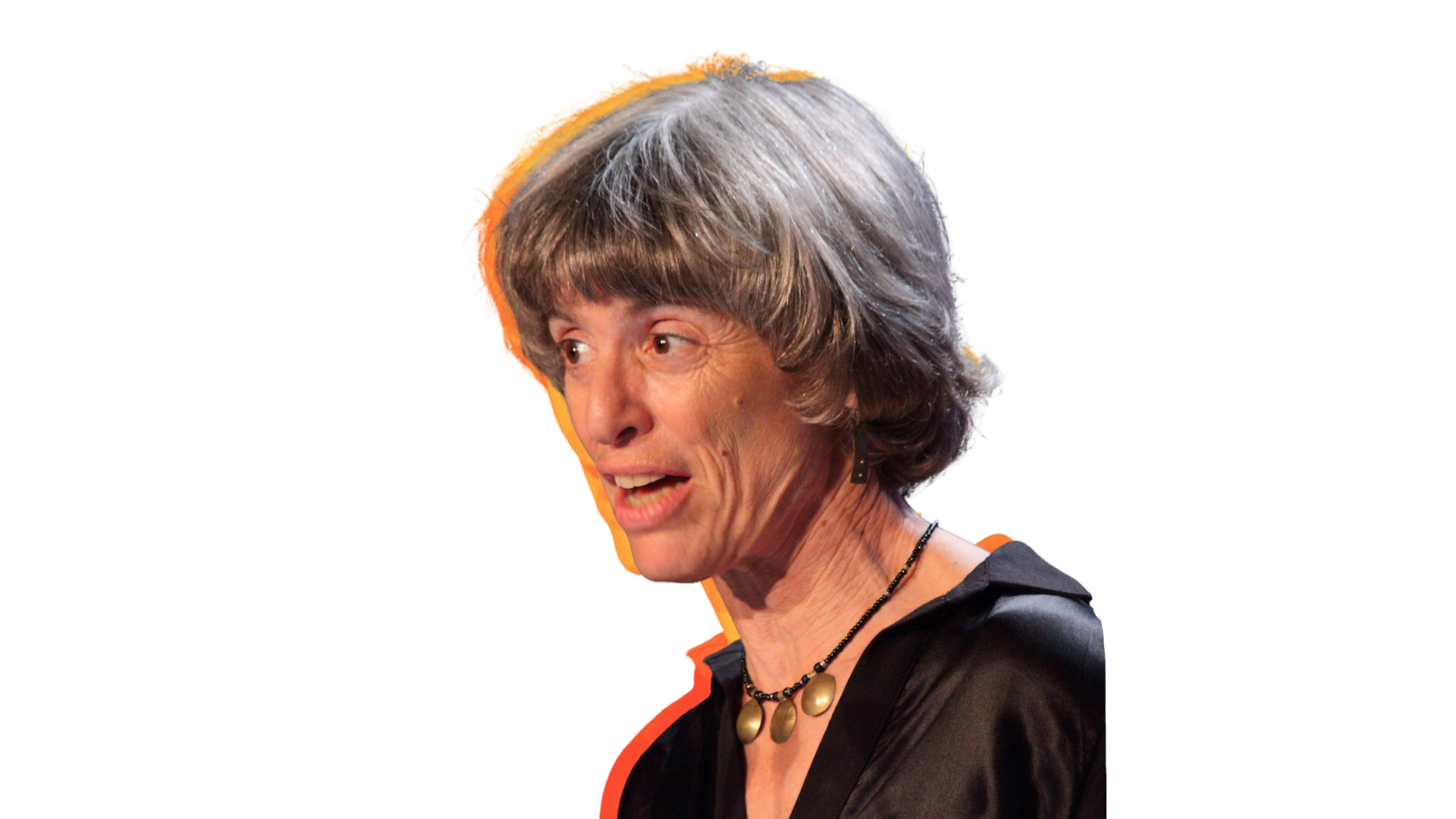

Unions Represent the Voiceless: Ruth Milkman

February 2nd, 2023

“Public opinion has become much more pro-union in recent years.”

Ruth Milkman is Distinguished Professor of Sociology and History at the CUNY Graduate Center and at the CUNY School of Labor and Urban Studies, where she chairs the Labor Studies Department. Her most recent books are Immigration Matters and Immigrant Labor and the New Precariat.

Unions remain a voice for the voiceless, especially given that the playing field has been very strongly tilted in favor of employers for some time. Employers are very aggressively anti-union, even in settings where union is long established like at UPS. The current wave of workers trying to unionize are not the usual suspects of historically unionized workers. They're mostly college educated, instead of blue collar workers, and they seek to address the gap between their labor market expectations and the actual job quality and pay that is available to them.

Read more about Ruth:

Follow Mila on Twitter:

Follow Future Hindsight on Instagram:

https://www.instagram.com/futurehindsightpod/

Love Future Hindsight? Take our Listener Survey!

http://survey.podtrac.com/start-survey.aspx?pubid=6tI0Zi1e78vq&ver=standard

Want to support the show and get it early?

https://patreon.com/futurehindsight

Credits:

Host: Mila Atmos

Guest: Ruth Milkman

Executive Producer: Mila Atmos

Producers: Zack Travis and Sara Burningham

-

Ruth Milkman Transcript

Mila Atmos: [00:00:04] Welcome to Future Hindsight, a podcast that takes big ideas about civic life and democracy and turns them into action items for you and me. I'm Mila Atmos. We are welcoming back Ruth Milkman to the show this week. She's a sociologist of Labor and Labour movements. And when we had her on the show back in April of 2018, she did an excellent job of explaining the role of unions and organized labor, how they're such crucial drivers of civic engagement, and how embattled both unions and workers had become. We spoke as a major case concerning public sector unions, was being weighed by the Supreme Court and amid a very hostile atmosphere to organize labor in general. At the time, Ruth wondered aloud.

Ruth Milkman: [00:00:56] I suspect if there is any kind of labor movement revival, it won't look like what we had in the heyday of the AFL-CIO, and it will look like something else yet to be imagined.

Mila Atmos: [00:01:07] Well, the unimaginable happened. A global pandemic upended work and life as we know it. And then inflation and workers organizing in new workplaces and new ways. According to reporting from Bloomberg Law, U.S. labor unions engaged in the most work stoppages in 2022 since 2005. And so I'm really delighted to welcome Professor Milkman back to the show to pick up where we left off, if you will, and to talk about some of her most recent work. Ruth Milkman is Distinguished professor of Sociology and History at the CUNY Graduate Center and at the CUNY School of Labor and Urban Studies, where she chairs the Labor Studies Department. Her most recent books are Immigration Matters, co-edited with Deepak Bhargava and Penny Lewis in 2021, and Immigrant Labor and the New Precariat from 2020. Ruth, welcome to Future Hindsight. Thank you for joining us.

Ruth Milkman: [00:02:04] It's great to be back with you, Mila.

Mila Atmos: [00:02:07] So as we talked last time, the Supreme Court had heard arguments in Janus, that big case concerning public sector unions, but the decision hadn't come down yet. As you predicted and as expected, the Court sided against the unions. And as we talk today, the Supreme Court has heard arguments in a big case

concerning organized labor. This one is Glacier Northwest V Teamsters. Can you situate us in the two cases and maybe explain their significance?

Ruth Milkman: [00:02:35] Well, they're very different because the law is different in the public sector than in the private sector. So the Janus case, which was decided, as expected against organized labor, basically prohibited requiring workers to pay what are sometimes called agency fees or fair representation fees if they worked in the public sector and were represented by a union but didn't choose to be a member of the union. That has been standard practice basically since public sector unionism took off in the late 1950s or early 1960s. But now it's not legal. So there were a lot of fears that the decision would lead to a precipitous decline in public sector density, and that actually did not happen. It's gone down a teeny bit, but not dramatically, partly because there was a lot of advanced notice that this was coming. And so the unions did a lot of work in the public sector to educate their members about why it was important for them to stay involved and so on. The other case is about the private sector, and if it's decided against labor, it will make it even harder than it already is under the National Labor Relations Act to successfully organize and become a collective bargaining agent on behalf of workers. It's really difficult now, so I'm not saying this decision doesn't matter, but it's kind of; it's less important, let's just say, than Janus was in terms of defining the big picture.

Mila Atmos: [00:03:59] We can safely describe this court as pretty anti-labor. Ruth Milkman: [00:04:02] Oh, no question. Yes.

Mila Atmos: [00:04:03] But is that in step with public opinion?

Ruth Milkman: [00:04:07] No. So what's changed since we last spoke is that not only have there been more work stoppages and some breakthrough organizing campaigns at iconic companies like Amazon and Starbucks, but public opinion has become much more pro-union in recent years. So it's up to about I think it's 70%, according to Gallup of respondents to polls, think unions are a positive force in America or that's not the way the question is asked, but something along those lines. So that is an all time high, I believe higher than any time since the 1930s, as long as they've been doing these polls. But it isn't matched by growing unionization. In terms of the numbers, just last week, the

US Bureau of Labor Statistics issued the most recent data on union membership in the United States and unionization rates for 2022, and it actually went down slightly in 2020 to very slightly like 1/10 of a point or so.

Mila Atmos: [00:05:00] Right. It went from 10.3 to 10.2. It's insignificant in a way.

Ruth Milkman: [00:05:04] It's insignificant, but the point is that the greater interest among both workers and the wider public in unionization has not come to fruition in terms of, you know, where it kind of counts, where the rubber meets the road in terms of increasing the number of workers covered by unions and collective bargaining. Many of the reasons for that do have to do with the broken labor law, which that case will lead to further deterioration of it.

Mila Atmos: [00:05:27] Right. Right. It's the labor laws that make it impossible almost to organize is what you're saying?

Ruth Milkman: [00:05:32] Well, we have the same basic labor law that was a big breakthrough when it was first passed back in 1935, almost a century ago, and that's called the National Labor Relations Act. And it was the first law to give private sector workers -- well, not quite all of them, but most private sector workers -- the right to collective bargaining and included various protections. For example, it's illegal still for an employer to fire a worker for being involved in union organizing or other -- the legal term is concerted activity so they don't have to be organizing a union. But if they're organizing collectively, they're protected in theory. In practice, employers fire workers for such activity every day, and the penalties are just considered a cost of doing business. And then in addition to that problem, through a series of legal cases and discovering loopholes and all kinds of different tweaks that have occurred over the 90 years since this law took effect, employers have found all kinds of ways to manipulate it in their favor. So the playing field is very strongly tilted in favor of employers, and that's been true for some time. So even though there's a lot of energy for organizing right now, and I think the pandemic has made the disparities between employers and workers, rich and poor, much more visible and, you know, increased general awareness of all that. It's not that easy to pull it off in practice on the shop floor, so to speak.

Mila Atmos: [00:06:57] Right. So in terms of the attitudes towards organized labor, why have those attitudes shifted? Like, why is there growing support? Is that the pandemic that essential workers were essential enough to risk, and in some cases have their lives taken, but not essential enough for fair pay and conditions?

Ruth Milkman: [00:07:15] To be honest, no one really knows the answer to your question. We can speculate. That's one thing I would point to. Another is the skyrocketing level of inequality that we've experienced in recent decades where, you know, the rich continue to get richer and working people can work 40 hours a week and still not earn enough to support their families. That's not a new fact, but there's greater and greater awareness of it, partly because of the pandemic and partly because everyone knows people who are in that situation. So, you know, the system is broken. And historically, unions were one piece of what limited the level of inequality. And as unionization has declined, which it has very dramatically since about 1980, it's not the only reason inequality has grown, but it's a major reason. And that, understanding that has led more people to think, yeah, unions would be a good idea,

Mila Atmos: [00:08:03] Right. Well, I was reading an article about UPS potentially going on strike if they don't get the contract that they deserve this year, 2023 is the year that they are renegotiating. And so, you know, one of the things that the article said was that while everyone stayed safely at home, UPS workers were delivering packages and UPS, the company, made billions. But workers got no hazard pay, no bonus. And I think everybody understands that. I think, you know, everyday people are not blind to this. That's for sure one of the reasons people support more unionization in general, but...

Ruth Milkman: [00:08:37] Well UPS has been unionized for a long time. So that's not new unionization. That's a struggle to improve the situation of an already unionized workforce. But that's also a struggle today. Employers are very aggressively anti union, even in settings where a union is long established. And in this industry, UPS is the only unionized major player. Right? Fedex is not unionized. Amazon certainly is not unionized and does a lot of its own delivery now. And so they feel that competitive pressure, and they will do everything they can to limit what they give in the way of benefits and pay to the workers and the union contract. And I'm not trying to excuse that, but you can understand that they feel under pressure. So in industries where the whole industry is not unionized or the bulk of it, you know, that's always an issue. Even

for unionized workers, for that 6% of the private sector that is unionized, it's still not so easy. One thing that has helped those workers in recent times, though, is the labor shortage that the pandemic helped create. So there were a bunch of strikes and they called it Striketober back in the fall of 2021 at big companies like John Deere, which makes agricultural equipment and Kellogg's. And again, this was not new organizing. These workers have been unionized for many decades. One of the things that has prevented strikes in sectors like that in the recent past is that it is completely legal to do this, and many employers do when they're faced with a strike, they may legally hire what are called replacement workers. And when the strike is settled -- if it is -- they are under no obligation to rehire the strikers. So that's a pretty strong obstacle to going on strike. And that's one reason why the number of strikes fell very dramatically since the 1980s, because it became common practice starting in the 1980s. Anyway. But in 2021 there was a labor shortage. John Deere had 10,000 workers that were about to go on strike. Where were they going to find 10,000 replacement workers? They couldn't. So those workers were emboldened by that situation and they did, you know, win some significant gains. And same with Kellogg's. Now, whether that will still be true when the UPS contract expires, I think it's in the summer, you know, we'll see, right?

Mila Atmos: [00:10:46] Yeah. Well, in terms of UPS, one question I have is if there is one big employer in an industry that has union workers, it raises the wages for everybody. But what I found interesting is that in this case, it really didn't raise wages for everybody because Amazon contracts out like piecemeal, by the hour.

Ruth Milkman: [00:11:04] That's right. So it can go the other direction, too. It can lower the wages for the unionized workforce. And that's the fear. If, you know, if the employer plays hardball in this case, you know, I have no idea what will happen. In the last UPS strike, I don't remember what year it was, but it was back when Bill Clinton was the president. They did pretty well. That strike was over a completely different set of issues to do with part time work and so on. So we'll see. The Teamsters Union, which represents the UPS workers, also has a new and more progressive leadership at the moment. So that probably is a factor as well. And they, recognizing the competition from low wage workers at Amazon and elsewhere, including those subcontractors you mentioned, I don't know how far this has gotten, but they are attempting -- the Teamsters -- to organize those workers right now to recruit the Amazon people. And that's sort of, you know, a recognition of the fact that they do have to do something in

the bigger industry rather than just represent the UPS worker. So that's... It's not really in UPS's interest to have a strike because they will lose a lot of business if that happens. So it's in their interest to to come to a settlement in a timely way. Many customers eagerly await the arrival of the big brown truck. And they know the drivers personally and all that. And so that's something the company should value and not want to jeopardize. But companies behave in strange ways, and I wouldn't venture to predict what will happen. But yeah, that's a big one that's coming up.

Mila Atmos: [00:12:19] Yes. Well, you talked about Striketober and there was also the great resignation. It does, as you say, feel as though a possible counterweight to the power of employers and the chasm of inequality. Is th tight labor market we're in right now.

Ruth Milkman: [00:12:35] Definitely.

Mila Atmos: [00:12:36] And building on some of what you said, you know, we have the lowest unemployment rate now in 50 years. How can non-unionized workers seize that opportunity?

Ruth Milkman: [00:12:45] Well, they're trying. I would just want to point out that it's a particular group of workers who are especially trying to unionize, and they're not the usual suspects of who's unionized historically. They're mostly college educated, not in, you know, blue collar, you know, manufacturing or construction kind of jobs or delivering merchandise, for that matter. And there's a gap between their labor market expectations and the job quality and pay that's out there. It's not that they can't find work. They can, as you just said, but the jobs they find after graduating from college and doing really well in school is a job at Starbucks or at the Apple store earning a little bit more than the minimum wage and being treated rather disrespectfully by the company. So I think that is a huge driver of what's happening now is that, you know, blocked aspirations for that population. And so we see it in a whole bunch of sectors and some of it isn't new. But since the pandemic, it's kind of blossomed in my own industry, higher education, for quite a while now. Adjuncts and graduate student workers have been actively organizing with quite a lot of success in terms of winning new unionization. And quite recently there have been strikes by those workers, too. Here in New York at the New School, where they won everything they demanded. And then at the University of

California, there was this huge strike of 48,000 graduate workers, which was maybe a slightly more mixed outcome, but it was fairly successful too. So so that's been happening for quite a while. But we see it in so many sectors, in nonprofits, in museums. Now at Starbucks, Apple, Trader Joe's, RBI, these kind of retail establishments that hire that type of worker. And I would argue that even the prepandemic wave of teacher strikes back in 2018 were also driven by this demographic. Teachers come in all ages, obviously, but the leaders of those strikes were in fact young millennials and Gen Z-ers, many of them Bernie Sanders supporters, who decided it was time to fight. And so that's what's driving a lot of it. So I think it's one explanation for the limited success they have had, which is that a worker like that, especially in a tight, tight labor market, is not so terrified of losing their job because they can always get another coffee shop job or whatever, or another retail job. They're easy to come by, at least for now, and it's not the job they really want anyway. And plus the fact that they are more educated and have more self confidence, perhaps based on their class background makes them a little harder to intimidate than some other workers might be. So those are all advantages that historically haven't really been there. And then finally, at places like Starbucks, Apple, et cetera, the companies have a kind of image to protect and a customer base that's not so different from the workforce they employ. And so they have a lot at stake in terms of not playing hardball too aggressively. They are doing it, but in a kind of quiet way.

Mila Atmos: [00:15:51] Mm hmm. Well, let's talk about Amazon. Let's talk about the other cases.

Ruth Milkman: [00:15:54] Okay.

Mila Atmos: [00:15:54] What is happening at Amazon and how is it different than, for example, is happening at UPS? You know, because at Amazon, it's really about the people working in the warehouse, correct?

Ruth Milkman: [00:16:02] Yeah. And also it's a completely non-union company today. So yeah, it's in the warehouse. The warehouse... Well, UPS has warehouse workers, too, by the way, so it's not completely.

Mila Atmos: [00:16:11] which are part of the union.

Ruth Milkman: [00:16:11] Yeah, but UPS has been organized for a long time. So that's like a whole other thing. Amazon is like a standard company, determinedly anti union. You know, the poster child for this used to be Walmart, which is also completely non- union. Walmart has kind of faded into the background a little more. And now the company everybody loves to hate is Amazon, although they still shop there. So maybe partly because for many years there was a pretty intense effort to organize at Walmart, which completely failed. Walmart was very adept at defeating it. No union has wanted to take on the challenge of organizing Amazon on a national scale because it is extremely daunting. It would cost a lot of money and staff and so on. So instead we've seen these kind of worker-led efforts, most notably here in New York and the Staten Island JFK Warehouse, where on April Fools Day of last year, the independent Amazon Labor Union won election. That victory has been certified by the NLRB. It's almost a year ago now. Amazon is still fighting back, claiming that the election was not legitimate. There's no basis for those claims, but they can delay and delay and delay and they will. And meanwhile, turnover in Amazon's warehouses is 150%. That's also the only victory to date that I believe it was that the company did not take the threat as seriously as they would have if they had understood how much support there was among the workforce there, which obviously there was, given the vote the way it turned out. They were much more successful in fighting the subsequent efforts by that same union to organize in upstate New York and across the street from the one that they won in. And then there's the Alabama case, which is kind of a slightly different story there. There was an established union involved, although the workers initiated it. They asked the retail wholesale department store union to help them. And so that's what happened. Some people argue that it's because it was an established union, that it wasn't as successful, You know. That workers don't respect established unions. I don't actually believe that. I think that because it was an established union, Amazon fought back more vigorously. And also the location is not, you know, a peripheral feature there, being in a right-to- work state like Alabama, where unionization is very limited and jobs that pay as much as Amazon pays are very hard to find. There were a lot of things that were really different from Staten Island so that they all contributed to that loss. I don't think there's any question that workers, if they really had a free choice and, you know, a free and fair election, as they say in the political sphere, were available to them, I think you would see a very positive union vote at Amazon warehouses, but that's not the situation. Instead, they are propagandized endlessly about why it's a bad idea to unionize. The

union organizers do not have the same opportunity or access to the workforce and all that is legal. They do illegal things too, sometimes. But within the existing law, there's a lot of stuff management can do to fight unions, and they routinely do. So it's not just Amazon. Any private sector company will do this, faced with that situation.

Mila Atmos: [00:19:22] We are taking a quick break to tell you about a fellow Democracy Group podcast. Swamp Stories. It's a great show that I think you'll be interested in. Swamp Stories, presented by Issue One, dives into political reform with a bipartisan lens exploring the problems facing our democracy and offering solutions. Hear elected leaders, activists, and experts from across the political spectrum discuss issues ranging from slush funds in Congress and dark money, to gerrymandering and election disinformation and, importantly, how to fix America's broken political system and build a better democracy. Find Swamp Stories wherever you get your podcasts or at SwampStories.org.

And now let's return to my conversation with Ruth Milkman.

But looking at the broader picture of labor right now and your recent work on immigrants, how does immigration fit into this picture? The right has carried out a fairly successful campaign of convincing white workers that immigrants are responsible for plummeting real term wages and worsening working conditions. So is there any truth to that?

Ruth Milkman: [00:20:33] I don't think so. I mean, I did write a book about this, and what I try to argue is the following. The sequence of events that leads to degraded work and lower pay and so on is as follows: Employers create jobs, not workers, right? They're the ones who set the terms of employment. Often they create jobs that white U.S. born workers shun. I'll give you an example, which is the meatpacking industry. There's many examples of this, but that's when I happen to know a lot about. Back in the 1960s that industry employed overwhelmingly U.S. born white workers. It was located mostly in the Midwest, places like Minnesota, Wisconsin, Chicago. And the industry restructured pretty dramatically, starting in the 1960s and among many other changes that they introduced they decided to move meatpacking closer to where the cattle were bred, which meant outside those regions, which are cold and not conducive to this sort of thing, and to places like Nebraska and Kansas and so forth. And that's

what they did. And I actually don't think the initial impetus was to fight unionization. But those states happened to be non-union, right-to-work states. Right-to-work meaning that union shops are illegal. Unions are much weaker in those situations. The unions did follow the work and successfully unionized some of those plants, but they were never able to get the same quality of contracts.

Ruth Milkman: [00:21:53] So the work was degraded in that industry. When this first began in the seventies and eighties, the companies did try to hire US-born white workers, and some workers tried the work and they hated it and they quit. Turnover was as high as 400% in some of these places. So then they started recruiting immigrants. They actively recruited them. It wasn't that immigrants showed up and said, "I want that job." They recruited refugees from Southeast Asia. They went south of the US-Mexico border and bussed people in. And pretty soon these jobs became, some people call them, brown collar jobs, you know, dominated by immigrants. And then actually later also US-born Black workers are part of the workforce in some places because now there's meatpacking in the Deep South as well. So the sequence of events is the job is degraded, US workers exit, hopefully for greener pastures, sometimes not. And then immigrants are hired in their place. So the actors here are the employers, not the immigrants who are just trying to survive. So, I mean, that's the essence of the story. There's a more complicated version in other occupations like housecleaning, childcare, paid domestic work. That's kind of a different story because those jobs were never good jobs. So there, it's also, though, a story of immigrants replacing US-born workers. In this case, mostly African Americans who voluntarily exit and abandon those jobs. And in this case, it's driven by politics, not industry restructuring. In 1964, the Civil Rights Act prohibited sex discrimination and race discrimination in the labor market, not 100% enforced, as we know. But that happened the year before the Equal Pay Act was passed, saying that for equal work, which hardly anybody has, but anyway, men and women should be paid the same. And for the first time, as a result of the civil rights movement and those legal changes, African American women were able to get jobs outside of domestic work, which had been kind of a ghetto occupation, literally. That that was one of the few jobs that was accessible to that population. So they started getting jobs in retail and restaurants and clerical jobs, not necessarily paying huge amounts of money, but because domestic work had the kind of legacy of slavery attached to it and because it can be quite degrading. Besides, a lot of people really hated that work and they just left en masse. It was an enormous exodus. Meanwhile, it's in this same exact

period, the 1970s, when inequality between classes begins its long trajectory upward. So you've got a lot of prosperous families wanting to buy their way out of domestic drudgery for whatever reason and looking for to hire... so demand is growing at the same time as the supply is disappearing and pretty soon they start hiring immigrants. The other factor that kind of contributed to this was growing labor force participation by married women and mothers who wanted someone to do the work that they had previously done in the home. So that also added to the demand and all these things are happening at the same time. So there it's not that a good job becomes bad and then immigrants take it, but a bad job stays bad and US workers move into better jobs. So to blame immigrants for any of that just is insane. In my view, they are as much the victims as the beneficiaries. You know, it's interesting to think about the success of people like Donald Trump in putting forward this argument that you should be blaming immigrants for your plight as a worker who's facing an unacceptable labor market situation. That argument has gone over especially well in formerly industrial areas where industries like steel and autos were the main activity economically and.

Mila Atmos: [00:25:36] They were union workers.

Ruth Milkman: [00:25:37] They were unionized, they were good jobs, quote unquote. They paid well, they were unionized. They had benefits, all the rest of it. The factories closed. You can't blame that on immigrants.

Mila Atmos: [00:25:45] Definitely not.

Ruth Milkman: [00:25:45] And immigrants go where the jobs are. So they actually don't go to those areas very much. And yet the argument resonates with a lot of the victims of that. So I feel like, you know, we have an educational challenge here to help people understand that the reason that they do face a very serious economic plight. They've experienced this dramatic reversal of fortune. But it's because of what employers do and corporate job mobility and public policy, not immigrants.

Mila Atmos: [00:26:16] Mm hmm.

Ruth Milkman: [00:26:17] Right now, with the labor shortage. You know, it's a very quiet movement, but a lot of employers would like there to be more people coming into the U.S. because they need workers.

Mila Atmos: [00:26:27] Yeah,

Ruth Milkman: [00:26:28] So it's very ironic. But the dominant discourse in a lot of

circles is, you know, immigrant bashing in this context. And that's really unfortunate. Mila Atmos: [00:26:35] Well, I think you did a really good job in the book.

Ruth Milkman: [00:26:38] oh thank you.

Mila Atmos: [00:26:39] Yes. In explaining that, you know, the people who create jobs are the companies and not the immigrants and not the everyday people who are the workers. And that this is a question of demand as opposed to supply. Well, I want to revisit something we talked about last time you were here, which is about how crucial unions can be to democracy. And we had the philosopher Jason Stanley on the show a while back and he talked about joining a union being a way to make politics material. In what ways can unions and organized labor invigorate our democracy, which, let's face it, could use some reinvigoration?

Ruth Milkman: [00:27:13] Well, I think there's two pieces to that question. One is democracy inside the workplace, which is a rare experience for US workers. But in unionized settings, there's a little of it in a non-union workplace, unless they are in a protected category like, say, they're black and experience blatant race discrimination, then they have some legal recourse. Or if they're a woman and they experience sexual harassment and they can document and improve it, say. They have some legal recourse. But if you're just in an unprotected category working in a private sector job, actually you have no rights at all, hardly in the workplace. If the employer just wakes up one morning and decides they don't like you anymore, they can fire you and there's no consequence. And that does muzzle workers voices in the workplace. They don't want to antagonize their supervisor or their employer because that's the likely result. And that's also why people fear union organizing, because that's often met with the same response. If you're unionized, you know, you can only be fired for cause. And if

something happens, if the employer does something that you object to, you can file a grievance. It's a much more democratic workplace environment. The other piece is that unions remain quite involved in the political system, and almost all of them have political action committees that are very active in electoral politics. In fact, part of the reason that the case you asked about before, the Janus case, exists is that right wing organizations that are eager to undercut the ability of unions to be political players recognize that while private sector unionization has gone down very, very dramatically in the last few decades, public sector unionism has been kind of flat. It's survived pretty well. So that's where the big money is in terms of large numbers of members. And so they go after the teachers unions, AFSCME, which represents federal, state and municipal workers and so on. So they were the ones who found the plaintiff for the Janus case. And so the motivation was actually to undercut the ability of unions to be political players. And, you know, with all their warts, unions do represent around 13 million workers, I believe, today in the United States. And all those workers do pay dues and that does give them both economic resources, but also they often are able to reach out to their members and encourage them to vote for a certain candidate and so on. They remain a political powerhouse despite their diminished numbers more than you'd expect given the low levels of unionization.

Mila Atmos: [00:29:49] Although I think reasonably limited. I mean, I read an article recently about how one union spent $25 million on like a PAC or something. And I just laugh because.

Ruth Milkman: [00:30:00] It's not very much.

Mila Atmos: [00:30:01] It's not very much money. You know, when people say, oh, you know, they're like Democrats or whatever. And then when you talk to, let's say, you know, really a right wing person with deep pockets, they write one $25 million check.

Ruth Milkman: [00:30:12] That's true.

Mila Atmos: [00:30:12] You know, it's not comparable against the unions where you know, pitching in $5 at a time or whatever it is, you know, and I just think it's it's just...

Ruth Milkman: [00:30:20] No, that's true. On the other hand, there are some bigger players like the employees union or the teachers unions who have deeper pockets than that. But still, compared to the old days when a third of U.S. workers were unionized, it's very modest. But it still makes a difference. And they remain a voice for the voiceless. You know, people who wouldn't otherwise have much influence on politics are represented by these organizations. It's true that their effectiveness is much weaker than it once was, but it's still a significant factor. And that's why some right wing organizations are so eager to destroy them.

Mila Atmos: [00:30:54] Yes. Yes. Well, I have a question about the recent rail worker dispute. We have a Democratic president who has long ties with organized labor who signed a strike busting law into effect in this latest rail worker dispute. It affects 115,000 rail workers. So how did that happen?

Ruth Milkman: [00:31:18] It's really an unfortunate story, and I'm not sure he had to do it. He felt that he did. So I think Biden's heart is in the right place. But the president alone can't do much to solve the bigger labor picture. In this case, the law that governs the situation is yet a third system than the ones we've talked about before. It's not the public sector laws, which are mostly at the state level. It's not the National Labor Relations Act. But it's another law called the Railway Labor Act, which has its own complex machinery. And because at that time the railways were seen as like vital economic arteries for the nation's economy as they still are, by the way, like airline workers are now covered by that law, too. So it's not trivial. But anyway, this case was involved railroad workers. So the law gives the federal government the power to intervene in a labor dispute in a much more immediate and draconian way than in other labor disputes. And so that's basically what happened. So in this case, the origin of the dispute is really in kind of a draconian employer move to restructure scheduling for these workers to the point where, you know, like getting time off to go to the doctor is like a major undertaking. And that's what the strike was about. It was not about money. You know, what sometimes called lean staffing. They kind of maximized that strategy in this industry. And workers were really, really aggrieved about it and the companies wouldn't budge. So the first stage in the story was the federal government mediated the dispute and came up with a compromise that they thought was reasonable, which was better than what the companies were offering. But then when the unions voted on it, some of them rejected it. And so the question was, what happens now? And it was also

about paid leave for like parents and stuff too. That was another piece of the dispute. So faced with that and the alternative being a strike that would disrupt an already screwed up supply chain, Biden bit the bullet and imposed that mediated agreement. And I was one of the signatories to a letter by a bunch of labor historians objecting to this and urging him not to do it. And I still think it was a mistake, but you can sort of understand why he did it. At the same time, given what the economic effect would have been of a strike. So, you know, it's a sad story.

Mila Atmos: [00:33:38] Yeah, well, it's incredibly sad.

Ruth Milkman: [00:33:40] And it's not that this has never happened in American history, but it hasn't happened for a very long time. And I don't think it had to happen. It seems like there could have been a better solution. But, you know, what do I know? I mean.

Mila Atmos: [00:33:50] Yes, yes, I know you're not president of the United States, but.

Ruth Milkman: [00:33:54] Well, and, you know, I think if Biden had the power to fix the National Labor Relations Act and the Railway Labor Act, maybe he would do something about it. But this has to come from Congress. And as we know, Congress is basically immobilized now over such things. So we're not going to get any relief on that score. And similarly, you know, Biden is a supporter of the various proposals that are out there for paid leave more generally for the entire workforce. But those are also going nowhere in this Congress, despite the fact that people of all political persuasions overwhelmingly support the idea. I mean, it's really amazing. So there are bunch of states and cities that have created paid sick leave and paid family leave programs, but getting it through Congress seems to be impossible.

Mila Atmos: [00:34:39] So I kind of want to pull two things together here. The Democratic Party being maybe less labor's enemy than the Republicans, but still not necessarily organized labor's reliable friend. And then to pull in that false narrative we talked about that the, quote, broken immigration system is responsible for declining living standards for American workers. And I wanted to pull these two threads together to ask about coalition building. It seems that these two are kind of self-reinforcing unless we figure out a way of turning organized labor into not just a popular force in American

life, but into a potent political coalition. Do you see that happening or how could you see that happening?

Ruth Milkman: [00:35:23] Well, it has changed a lot. So when I first started studying this stuff, the relationship of immigrants to organized labor back in the 1980s, a lot of union officials were extremely hostile to immigrant workers. They kind of bought into that narrative that immigrants were to blame for declining living standards for US-born workers. And that has dramatically changed to the point where the vast majority, not 100%, but probably three quarters or something of union officials and staffers and so on, recognize that that was a mistake. And that the answer is to organize immigrant workers, not to be hostile to them or to try to exclude them, which is kind of hopeless anyway. So that is completely turned around. And as a result, there's been a significant amount of unionization among immigrant workers. The difference in unionization rates is now trivial. It used to be quite substantial. And then there have been efforts at that kind of coalition building as well. Most recently, I think this is kind of under the radar, but it was reported a little bit in the news. There's a new regulation that prohibits deportation of immigrant workers who experienced labor violations. This is just new. It happened like a couple of weeks ago. And it's something that that kind of coalition campaigned for quite successfully. So, you know, that's a regulation. So you don't need Congress. It's an interpretation of the existing law. And it may not survive if the Republicans take over the White House in the future. But for the moment, that's in place. It's like DOCA that way. The deferred action thing, that's what it basically offers is deferred action for immigrants. In that situation, if they've been paid less than the minimum wage, for example, which happens a lot or other legal violations in the workplace, they have some protection on the immigration front. So that's something I do think that there's growing recognition that, you know, these are allies that need to work together and it's still very challenging given the congressional gridlock and so on. But I think we're beginning to see more and more of that.

Mila Atmos: [00:37:18] Hmm. Well, we're a show about civic engagement. So what are two things an everyday person could do to, you know, demand fair pay, fair hours, you know, to have even -- if you cannot advance more unionization -- but to advance that kind of standard.

Ruth Milkman: [00:37:37] Well, pay attention to what's happening in the world. If there is a union campaign in your community, do what you can to support it and recognize it. Let it be known to employers who are mistreating workers that you don't want to patronize their businesses if they continue to do so. Those are some things that people can do and, you know, vote for politicians who support these kinds of things. You know, there are quite a few of them.

Mila Atmos: [00:38:03] Here's my last question. Looking into the future, what makes you hopeful?

Ruth Milkman: [00:38:09] I think the main thing is this new generation that we were talking about before that is doing the union organizing. And they're not just doing that. They are the demographic propelling movements like Black Lives Matter and MeToo, to a great extent and so on. And this is a generation whose view of the world has been shaped by things like the Great Recession that began in 2008, when many of them came of age again after doing everything they were meant to do. Going to college, graduating from college, and then they faced the post Great Recession labor market and end up working at Starbucks or whatever. And between that and other kinds of disillusion that they faced. 2008 was also the year that Barack Obama was elected, and people thought we were entering a period of a post-racial society. And then we see police murdering Black people all over the place. And that got this generation's attention as well. If you look at the demographics behind these social movements, actually starting with Occupy Wall Street, which is when it first became clear to me because I did some research on that which appeared right here on our doorstep in New York in 2011. That's who the leaders of these movements are. They are college-educated young people, and there are a lot of them because these younger generations are more educated than any previous US generations. And they really do have a different view of the world. They see the world in what they call intersectional terms. That is, they see the connections between not only immigration but race, gender, sexuality, and capitalism; and they're pretty critical of it. So that's what makes me hopeful, is that they are the future. That's the generation that eventually is going to take over the country. And so I guess that's one thing that makes me hopeful.

Mila Atmos: [00:39:50] Well, thank you very much for joining us on Future Hindsight, Ruth. It was really wonderful to have you on.

Ruth Milkman: [00:39:55] It's my pleasure. Thanks for having me.

Mila Atmos: [00:39:58] Ruth Milkman is Distinguished Professor of Sociology and History at the CUNY Graduate Center and at the CUNY School of Labor and Urban Studies, where she chairs the Labor Studies Department.

Next week on Future Hindsight, I'll be speaking to Octavia Abell. She's the co-founder and CEO of Govern for America, a nonprofit that works to bring the next generation of leaders into government. We always talk about how you can get engaged beyond voting, but short of running for office. But what about actually working for the government? We're talking public service in the civil service. That's next week. On Future Hindsight.

And before I go, first of all, thanks for listening. You must really like the show If you're still here. We have an ask of you. Could you rate us or leave a review on Apple Podcasts? It seems like a small thing, but it can make a huge difference for an independent show like ours. It's the main way other people can find out about the show. We really appreciate your help. Thank you. This episode was produced by Zack Travis and Sara Burningham. Until next time, stay engaged.

The Democracy Group: [00:41:19] This podcast is part of the democracy group.